Emily Cox is a fourth-year PhD Candidate in the History of Art specializing in nineteenth-century European art with a particular focus on France, Britain, and Russia. Her dissertation re-imagines the relationship between art and politics in the fin de siècle. An “intellectual history of objects,” her project casts a transnational gaze across 1890s cultural forms — wallpaper, ceramics, paintings, novels, treatises — to argue that the period’s critical and aesthetic possibility lay in its fundamental interdisciplinarity. Her research questions center on radicality, periodization, and form; discipline and disciplinarity; ekphrastic writing and critical theory; and the historiography of modernism.

With the support of a European Studies Council Fellows Award, I was able to present “Fabergé’s Imperialism: Decorative Worlds and Utopian Dreams at the Exposition Universelle of 1900” at the Association for Art History’s annual conference from April 12-14, 2023, in London, U.K. My paper was part of the panel “Deconstructing Russian Imperialist Aesthetics: Repression, Resistance, and Representation in the Long Nineteenth Century.” Alongside presentations on the Ukrainian nationalist etcher Taras Shevchenko, networks of Jewish and Ukrainian expat painters in turn-of-the-century Paris, and exhibitions of indigenous objects from Russia’s northern territories at World’s Fairs across Europe, my talk asked how we might begin to decolonize Russian nineteenth and twentieth century art.

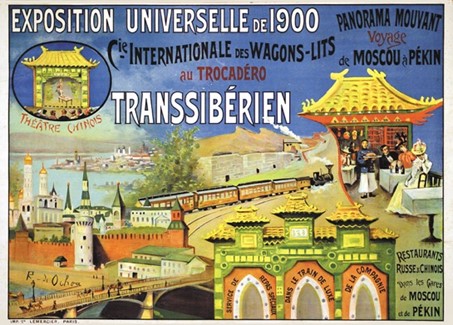

Based on lengthy archival research, my paper considered Peter-Carl Fabergé’s Trans-Siberian Railway Egg (Fig.1) as a microcosm of imperial bravado. Its “surprise,” a golden wind-up train, loops around a map incised on the egg’s surface illustrating the eastern imperialism on which late nineteenth-century Russia staked its future. Borrowing techniques from Japanese netsuke, Fabergé’s works used materials extracted from across the Russian Empire, indexing the coeval rise of Russian militarism and decorative arts. Through its material make-up, the Trans-Siberian Railway Egg embodies Russia’s imperial ambitions at the close of the nineteenth century. Crafted during a period of heightened political tension with Japan and China, it was part of Fabergé’s display at the Exposition Universelle of 1900. There, its political import and emphasis on interactive play was echoed in the Panorama Transsibérien (Fig.2) at the Trocadéro.

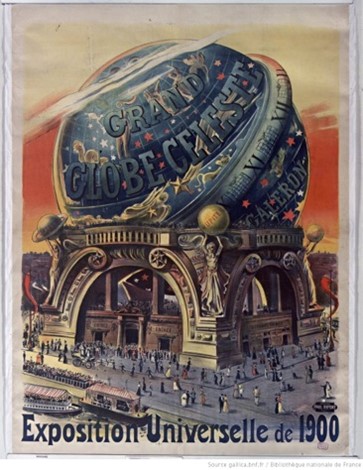

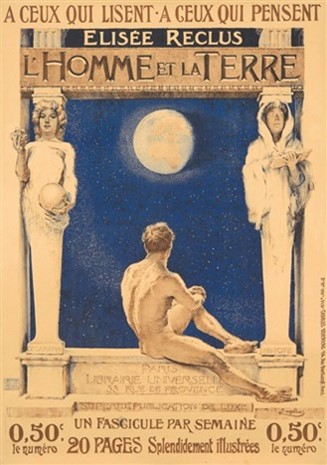

From Fabergé’s display, fairgoers could not have missed one other globe whose size trumped all others: a cyclorama built on plans by anarchist geographer Élisée Reclus (Fig. 3). Reclus was a vehement denouncer of Russia’s eastward expansion. Drawing upon his bioregionalist thought (Fig.4), the “Grand globe” was meant to liberate spectators from the nationalist and imperialist cartography on view below. Setting Fabergé’s miniature globe against Reclus’s monumental one, I ask: what were the stakes of such microcosmic imaginings – playful and political – at the turn of the century? In the global landscape of the Exposition Universelle of 1900, I argue that decorative art (on all scales) assumed an unexpected but critical role in materializing utopian and imperialist visions for the twentieth century.