Mireille Pardon, Ph.D. Candidate, History Department, in Bruges, June 2019

Thanks to funding from the MacMillan Center, I have travelled to Belgium this summer to continue my dissertation research on crime and punishment in late medieval Flemish cities. The Late Middle Ages were an exciting time for Flanders — Bruges and Ghent were international trading centers, townsmen asserted their rights against the Duke of Burgundy, and artists such as Jan van Eyck flourished. My research, however, focuses on the lives of men and women who rarely entered the historical record. In records of criminal prosecutions, we can catch a glimpse of everyday interactions in a medieval city: a tavern brawl, a wayward cow grazing in a neighbor’s field, or a merchant defrauding their customers. My dissertation uses these records to look at cultural ideas and stereotypes about crime in fifteenth-century Bruges and Ghent.

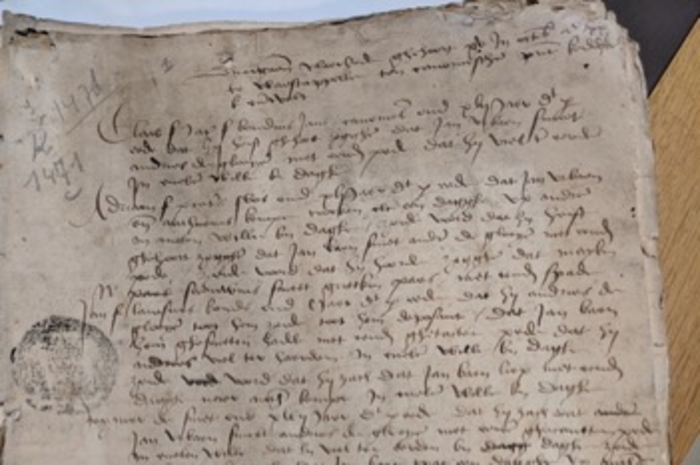

On this trip to the archives, I have had the opportunity to look at an exciting new source: the “doorgaande waarheid” (passing truths) at the State Archives of Belgium in Bruges. As a means of investigation, a judicial official would ask people a series of questions about potential crimes in their local community and record their responses. What a fascinating resource for the thoughts and experiences of everyday people in the medieval world!

Doorgaande waarheid

Doorgaande waarheid

In this record from 1471, we see several people giving their opinion on the same event: a fight between Jan Urbaen and Andries de Gloeyere. The first man, called Clais, reports that Jan struck Andries so hard that he fell and he did it “in evele wille” (with evil intent). But this is just information that he “heeft ghehoort zegghen” (had heard tell). Jan son of Lamsins, the third respondent, corroborates this series of events, having heard the story from the victim, Andries de Gloeyere, directly. This trip was the first time that I have gotten to see the records of the “doorgaande waarheid” and I am excited to be able to add this new source to my project.

The main sources for my dissertation are bailiff accounts that recorded the fines that the bailiff collected as well as the payments made to the executioner for carrying out punishments. The majority of crimes during this period were resolved through a fine rather than a corporal or capital punishment. However, the fifteenth century was a period of transition: a judicial system based on fines and rituals of reconciliation gave way to a system built around spectacular punishment. This transition coincided with an individualization of prosecution, as collective responsibility and smoothing community relationships transformed into the individual’s culpability before the state. In general, my dissertation looks at tropes of violence and explores how changing cultural ideas about interpersonal violence influenced the development of early modern spectacular justice.