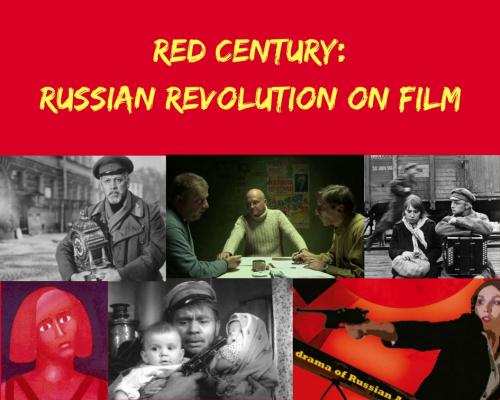

The series Red Century: Russian Revolution on Film commemorating the centennial of the 1917 Revolution continued throughout the Spring semester. Six films shown in the second part of this series were made long after the Revolution itself, the earliest ones being dedicated to the 50th anniversary of it. The series closed with two contemporary works, Angels of Revolution and For Marx, filmed after the Dissolution of the Soviet Union—in 2014 and 2012 respectively.

The first film of the series, Comissar (Комиссар, 1967), was introduced by Chloe Papadopoulos, graduate student in the department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, who talked about the history of the film’s reception and Askoldov’s fate, as well as, the cast’s performance, artistic aspects of the film, and intertextual references. A story about a woman commissar who finds herself pregnant as the Civil War goes on and is faced with a difficult choice. Comissar is Askoldov’s first and only work: it was his final student project at the Higher Courses for Scriptwriters and Directors. Although based on Vasily Grossman’s short story In the Town of Berdichev, the script departs from it in many aspects. In fact, Askoldov was forced to make significant changes in the script but then shot according to his original conception; as a result, the film was shelved for twenty years. Among the reasons why the film was censored was its representation of the Jewish people during the Civil War: as Papadopoulos points out in her notes for the film, Askoldov frames the ‘Magazannik family’s existence as an endless series of pogroms.’ Askoldov’s sympathy for the Jewish people is deeply connected to his biography: when he was a child, both his father and mother were arrested, and he left home looking for shelter at his parents’ friends’—a Jewish family. In spite of that, some viewers found Askoldov’s work anti-Semitic in itself, seeing Rolan Bykov’s performance as caricature.

Commissar was shot in 1967 to commemorate the Revolution’s fiftieth anniversary; so was the next film in the series, Seventh Satellite by Aleksei German and Grigori Aronov. This work was introduced by Valeriia Mutc, graduate student in the department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, and Sergei Antonov, Assistant Professor of History. The directorial debut by one of the most famous Post-Soviet filmmakers, Seventh Satellite was an adaptation of the eponymous 1927 novella by Boris Lavrenev. The protagonist, a Tsarist Army General Adamov, is briefly arrested during the Red Terror. Even though he is set free, his life has irreversibly changed and is, as Mutc states in the program notes, “inexorably pulled into the orbit of something greater than himself.” Although the film still appears stylistically bold, many of German’s artistic experiments were met with resistance—often successful—from his co-director, Grigori Aronov. By 1967, Aronov already was an accomplished director who knew the system well and was careful in his creative choices. As if in line with the discrepancy between the approaches of the two directors, the film was first shown on the state television and soon banned on the very same channels.

German’s film was followed by another adaptation, Vladimir Fetin’s The Tale of Don (Донская повесть, 1964) introduced by Ana Berdinskikh, graduate student in the department of Slavic Languages and Literatures. Yakov Shibalok is a Cossack who is trying to take care of his baby son while fighting for the Red Army but finally gives up and takes him to an orphanage, which is where we begin his story. Berdinskikh discussed the short story by Mikhail Sholokhov on which the film was based, the intertextual references, the historical context, and the unusual casting decision: Yevgeny Leonov, who played the leading role in the film, was famous for his comic performances, and two years later, he would become the iconic voice of the Soviet Winnie-the-Pooh. Berdinskikh argues that this casting choice could be seen as “an attempt to abate some of the brutal and problematic aspects of Shibalok’s character (as well as the Civil War, more broadly).”

The next film in the series was Alexey Fedorchenko’s latest film to date, Angels of Revolution (Ангелы революции, 2014). In her introduction for the film, Dasha Ezerova, graduate student in the department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, pointed out several cinematic influences on the film, which include Sergei Parajanov, Akira Kurosawa, and Wes Anderson. She talked about the historical context of the events depicted in the film. Despite its theatrical style, Angels of Revolution is based on real events of the 1934 Kazym uprising: the rebellion of the indigenous people of western Siberia, Khanty, against the Soviet policies of collectivisation. The film tells the story of a group of revolutionaries sent to the tundra to “civilize” the locals. To do so, they not only try to educate the Khanty population but also introduce them to the Soviet Avant-Garde. The juxtaposition of the Avant-Garde art and the Khanty culture underlines “the corrupt nature of cultural legitimation weighted in the favor of the imperial center,” according to Ezerova. At the same time, this juxtaposition also draws a parallel between the two cultures in question, as the Avant-Garde would soon fall out of favor with the Soviet authorities, and many artists would suffer the same fate as the rebellious Khanty.

No Path Through Fire (В огне брода нет, 1968) took us back to the Civil War times. Tanya Tyotkina works as a nurse on a hospital train, tries to find love and understand people around her and the ideas they are fighting for, all of which is not very easy. Her life changes when she meets an artist and discovers a talent in herself. In the end, she is faced with a difficult choice: would she be brave enough to die for the Revolution? The film was presented by Spencer Small, graduate student in the department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, who talked about the particular role of the trains in the Revolution, Tyotkina’s drawings in the film, and the casting process. The director, Gleb Panfilov, wanted the leading actress to be not too good-looking, and he chose young Inna Churikova for the Tyotkina’s part. Panfilov and Churikova continued to work together after No Path Through Fire and got married.

For Marx… (За Маркса…, 2012) was a perfect film to end the series as it deals with the legacy of the Revolution in the context of current workers’ protests in Russia. As Professor Marijeta Bozovic, who introduced the film, pointed out, the film borrows its title from the 1965 treatise by Louis Althusser, who “opens with a critique of contemporary French Marxist thought, highlighting the absence of a native leftist philosophical tradition <…> and looking to establish a more robust direction for future inquiry in what he termed the mature texts of Marx, over the earlier idealist-inflected works.” Svetlana Baskova, the director of the film, tells the tragic story of an independent union at a steel mill. Although the film is quite graphic at times, it shows “relative restraint” in comparison with other works by the director, as Professor Bozovic notes: Baskova is famous for her shockingly violent video art. By stepping away from that aesthetic, Baskova is now able to reach a broader audience, and it is clear that it was her intention: she organized screenings in provincial cinema clubs which were attended mostly by activists and local workers. According to Baskova, this audience received the film warmly and was eager to discuss it; the same applied to the audience at the Whitney Humanities Center.

The Red Century: Russian Revolution on Film series indeed covered almost a hundred years, starting with Eisenstein’s Strike (1925) and ending with two films from the first decade of the 21st century. Over the series, we could see how the discourse on the Revolution changed with time, and the diverse range of works included documentaries, adaptations, classics, and contemporary films.

The series was sponsored by the Russian Studies Program of the European Studies Council at the MacMillan Center, the Whitney Humanities Center, and the Edward J. and Dorothy Clarke Kempf Memorial Fund. We hope to see you at the new Russian Film Series screenings next year.

Written by Mariia Muzdybaeva, a graduate student in the European and Russian Studies Masters program